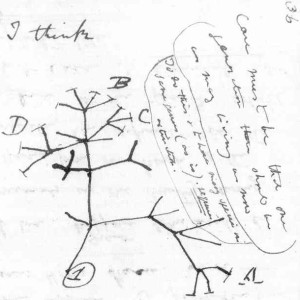

Most of us can tell stories. It’s our normal mode of relating what we did at the week-end or last night or when teasing someone about the office party. Or why we arrived home a few hours later than promised. These different stories may contain varying levels of truth and exaggeration, of course, but they tend to share a structure that the audience of the tale understands (even when not being entirely sympathetic).

If you’ve ever followed the instructions to programme the DVD recorder or build a flat-pack shelving system, read a typical ‘look at us’ brochure or website, or glazed over while digesting a vacuous press release or white paper, you will have experienced fully the benefits of grown up and serious writing first hand.

And that’s what they inflict on their customers.

In a lot of companies, the state of internal communications can be just as bad, if not worse. Not only do we need to find ways to use stories to connect to customers, I think it is equally important to tell stories within business.

Stories connect people and I believe it is a rare person who does not have a natural ability to do it. It is the corporate fear of openness and honesty that demands we lose the emotion and the fun when we discuss business.

In Made To Stick, Chip and Dan Heath talk about Xerox engineers gathered for a game of cribbage. One of the repair engineers discusses – over time – a peculiar fault uncovered after a recent ‘improvement’ in the electronics. The story gets told, the other engineers take it on board – and they remember it for when they might face a similar situation. This story was not – and could not – be replicated in a procedure manual. At least, not in a way that would have made it so memorable. (Read my review of Made To Stick.)

Therein lies the problem: many companies not only discourage (actively or passively) the storytelling approach to conveying information but they also have no processes in place to capture stories should they come to accept their importance.

Would the stories dry up if employees thought they were being captured? That’s a risk that stems primarily from the fact that many people are locked into thinking that business writing is an artificial construct that only skilful practitioners can master. Encourage people to find and use their own voice and free themselves from the belief that there is a special way to write that is so different to the way they speak and much of that paralysing fear will disappear.

It is up to companies to implement tools that allow the writing of stories in ways that retain their spontaneity and flexible structure. Social tools such as blogs and forums are perfect for such a thing. These can remain on an intranet for all good and proper business and security reasons but at least a repository of expertise and company knowledge will have a place to reside.

Pipe dream or necessity? How do you see the future of stories in your business?